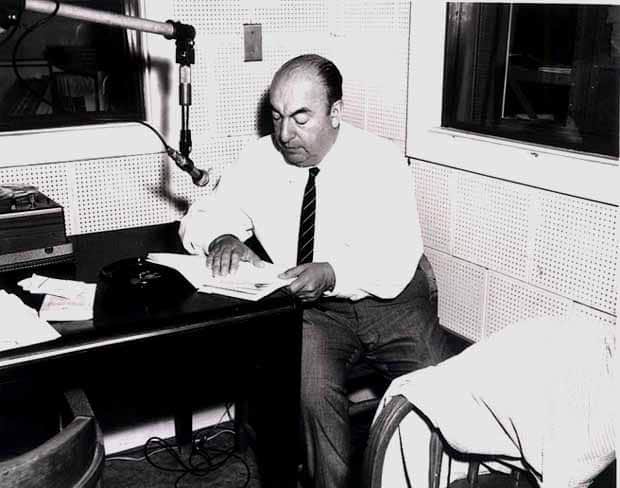

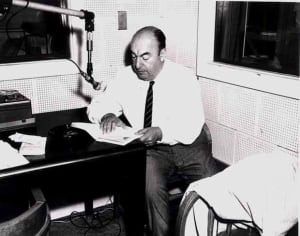

Pablo Neruda, born on this day in 1904, is internationally recognised by many readers for his profound and diverse poetry. The subject matter of his work is extensive, ranging from lyrical celebrations of his native Chile to more sombre versifications on love, mortality and the ultimate transience of the human experience. Perhaps more significant, though, is Neruda’s recurrent emphasis on the importance of memory and time in shaping our response to events which, inevitably, will affect all of us at some point in our lives.

Suffering bereavement is, unfortunately, one such event that will be experienced by each and every one of us. However, as celebrations of lives well-lived continue to demonstrate, it is in no small part through the act of remembrance that we can begin to reconcile with our grief and move forward beyond the absences left by the loss of our loved ones.

Although often overlooked in the everyday life of many people, poetry often acts as a spiritual balm for families during their most fragile moments. Even if we are not regular readers of poetry ourselves, it is often the case that the linguistic deployment of certain phrases, words and images can help us in giving positive expression to the heartfelt pain and emotion brought about by death. By reading poetry, we feel less isolated; we become connected to a universality of feeling that is usually contained in the private thoughts of others. Thinking about how someone else has dealt with their grief can bring a particular reprieve to our own personal hardships, and it is for this reason that poetry often plays a central role in the funeral service.

The process of grieving undoubtedly brings about contemplations of our own mortality, but such thoughts need not lead us further into despair. Indeed, in Neruda’s poem And How Long? the poet uses the motif of time to propose a string of probing questions that seek to force a reconsideration of traditionally accepted perspectives on life and death:

How long does a man live after all?

Does he live a thousand days, or only one?

A week, or several centuries?

How long does a man spend dying?

What does it mean to say ‘for ever’?

If Neruda’s questions provoke deeper thinking about life, loss, memory and time, then poet Brian Patten’s work, So many different lengths of time, provides us with a simple and heartfelt answer to these questions. By opening his poem with the above verse by Neruda, Patten establishes an immediate thematic link to the Chilean poet, but goes beyond the Chilean poet by seeking to overcome the looming finality of death. Patten’s poem argues that it is the act of remembrance which offers family members the best antidote to the anguish of loss. In tackling the subject of grief, Patten views poetry as performing an important social function: ‘Poetry helps us understand what we’ve forgotten to remember. It reminds us of things that are important to us when the world overtakes us emotionally.’

If Neruda asks, ‘How long does a man live after all?’, then Patten provides us with the simplest of answers: ‘A man lives for as long as we carry him inside us’. Although death brings much uncertainty and grief in its wake, the memories that we share with our families about those we have lost is no small consolation. As time unfolds, the importance of remembering those we love increases, and by talking, laughing and sharing stories with other people, we can ensure they remain with us forever. Patten’s poetry suggests that our dearly departed can attain a form of immortality through a continued presence within our thoughts and memories. In revisiting Patten’s poem on the anniversary of Pablo Neruda’s birth, we should take comfort in the knowledge that remembrance of the past –and of memories shared with those we have loved and lost– gives us a means of getting beyond grief and moving forward in our lives.

So many different lengths of time, Brian Patten

How long does a man live after all?

A thousand days or only one?

One week or a few centuries?

How long does a man spend living or dying

and what do we mean when we say gone forever?

Adrift in such preoccupations, we seek clarification.

We can go to the philosophers

but they will weary of our questions.

We can go to the priests and rabbis

but they might be busy with administrations.

So, how long does a man live after all?

And how much does he live while he lives?

We fret and ask so many questions –

then when it comes to us

the answer is so simple after all.

A man lives for as long as we carry him inside us,

for as long as we carry the harvest of his dreams,

for as long as we ourselves live,

holding memories in common, a man lives.

His lover will carry his man’s scent, his touch:

his children will carry the weight of his love.

One friend will carry his arguments,

another will hum his favourite tunes,

another will still share his terrors.

And the days will pass with baffled faces,

then the weeks, then the months,

then there will be a day when no question is asked,

and the knots of grief will loosen in the stomach

and the puffed faces will calm.

And on that day he will not have ceased

but will have ceased to be separated by death.

How long does a man live after all?

A man lives so many different lengths of time.