Last week the BBC ran a program called A Time To Live. A wonderfully touching display of death positivity that’s at times bitterly heart-wrenching, and at others hilarious; it’s a program well worth watching, reminding us that there can be beauty and dignity in death and end of life.

A Time To Live explores the stories of 12 individuals, all of whom have been diagnosed with a terminal condition that severely limits the time that they have left with family and friends. Ranging from twenty years old to seventy, the interviewees are diverse and unique, each providing the viewer with a completely different context, circumstance and way of processing the information they are forced to contend with. It provides a positive voice while answering the valuable question: ‘what do you learn about life, when you’re facing death?’

Bookending an hour-long exploration of what it means to live with a terminal illness, film maker and narrator Sue Bourne twice makes the suggestion that her film isn’t about dying at all, and is in fact primarily concerned with living. Although death plays a major role in the documentary, it’s a testament to those involved, both interviewer and interviewee, that her assertion rings true.

Watching A Time to Live, we reflected on how as human beings, we will respond to news of our imminent death in an almost infinite number of ways. Whereas our first interviewee, Fi, decided to return to work after her diagnosis, determined not to let her illness dictate how she lived the last months of her life, others retire early to spend time with their family, take time off to travel the world or turn to long distance running.

Bourne is careful not to make any moral judgement about the decisions taken by the 12 participants and though the viewer is sometimes left feeling as though a particular individual’s response to the situation would be at odds with their own, each is presented in an understanding and sympathetic manner that leaves you stunned at how consistently humans respond to adversity with strength and dignity. The interviews are so dextrously handled that the program never feels voyeuristic, rather you are made to feel as though you have been invited into the front room of the subject.

Many of the interviewees also offer a unique insight into some of the lesser discussed issues surrounding untimely death. There are segments concerned with topics like dying with regrets and the desire to make things right, with planning for the future of a family, with how you measure the worth of a life, and with how you choose to spend the remainder of your time.

Throughout it all, the intensity of being confronted by one’s own mortality is a recurrent theme. For some, it’s the catalyst for drastic change, for others, it renders the world more significant and detailed, with every moment to be savoured. For everyone involved, it appears to require a radical reappraisal of what we think we know and the way in which we approach life.

Discussing the subject with 12 participants highlights how necessarily different our coping mechanisms must be. A young twenty-something who hasn’t had a long life cannot process their mortality in the same way as a seventy-year-old who feels that they’ve made the most of their many years. Likewise, someone without children will have to deal with a very different type of grief and pain when compared to someone with a young family. For some, faith provides a framework through which to understand their situation, while for others friendship or companionship prove invaluable.

A Time to Live is a thoughtful and insightful exploration of how people continue to live and struggle, despite the end being close at hand. Some watching might find the program’s honest display of humour, sadness, joy, fear, positivity and strength to be a testing rollercoaster of emotions, but these will, by the end, all be surpassed by an overriding sense of awe at how capable human beings are of facing extreme hardship head on. With A Time To Live, Bourne has created a television show that provides us with an opportunity to understand what other people are feeling and coping with at the end of their lives, while also forcing us to take a long, hard look at our own attitudes towards life and death.

From all of us here at Beyond, we’d like to offer our best wishes to the 12 individuals depicted and their families.

A Time To Live is available on BBC iplayer until June 16th.

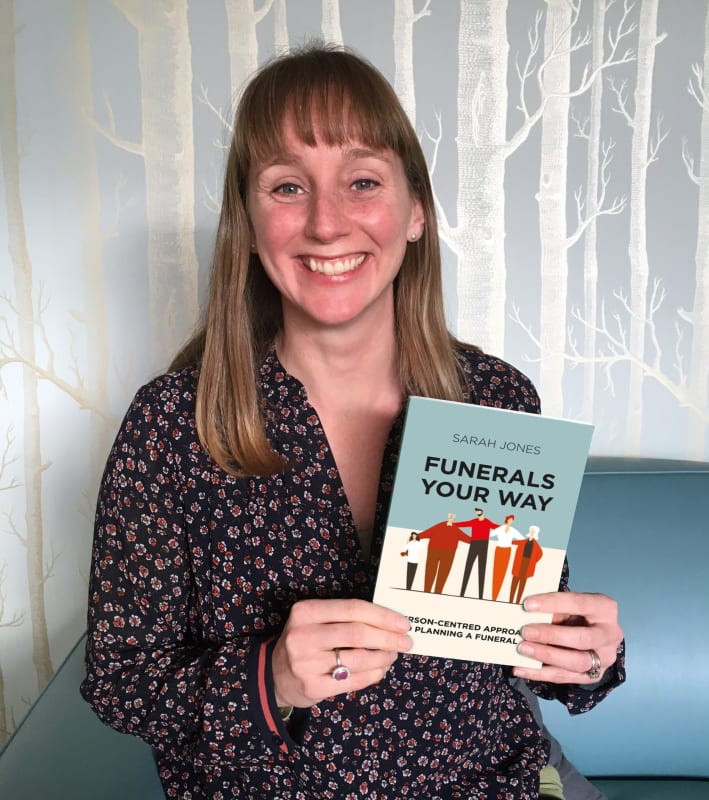

If you are nearing the end of your life, you may wish to consider a funeral plan. This can ease the financial burden of a funeral, while also ensuring that your funeral will be as you want it to be.